The Amazon

Rainforest as a vital carbon sink

The Global

carbon cycle essentially refers to the exchange of carbon between the Earth’s

various carbon reservoirs. There are 5 main reservoirs (The Earth’s interior,

the atmosphere, the biosphere, the oceans and the sediments) which are all

interconnected by pathways of carbon exchange.

Changes in

the carbon cycle can be environmentally devastating. Indeed, perhaps one of the

greatest threats encountered by humans is the ever increasing amount of carbon

released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels. This additional

carbon reacts with oxygen to form carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas which has

been responsible for the recent rise in global average temperatures. As the

amount of carbon increases in the atmosphere other carbon sinks become more and

more important in buffering and controlling this increase.

Consequently,

the Amazon rainforest plays a crucial role in the global carbon cycle as it

acts as a carbon sink (which refers to an area’s ability to store and absorb CO2

from the atmosphere). Indeed, as trees grow they absorb much more CO2

(in the order of hundreds of millions of tons) than is released by tree death. Consequently,

the Amazon holds 17 percent[1]

of all Earth’s terrestrial vegetation carbon stock.

However,

human impacts have put the rainforest under an increasing amount of strain both

directly through rapid deforestation and indirectly through changes in climate

patterns caused by warmer global temperatures.

The Amazon has

witnessed an increasing amount of droughts in the past decades which is in part

caused by an increase in El Nino events which leads to dry conditions in the

northern Amazon[2]. Consequently, average rainfall levels dropped

nearly 3.2 percent per year between 1970 and 1998[3]

in the Amazonia region. There have also been extensive dry periods such as the

ones in 2005 and 2010 which lead to basin wide losses in biomass.

The 2010

drought for instance, lead to a higher biomass mortality rate and a lower

biomass productivity rate[4].

There was also an increase in wild fires due to the dry conditions. As a result, it has massively reduced the

Amazon’s ability to act as an efficient carbon sink as the forest essentially

became carbon neutral (meaning that it is absorbing as much carbon as it is releasing).

Unfortunately,

the effects of a drought are not only catastrophic in the short term but they

are also alarming in the long term. Indeed, the effects of a drought such as

the one in 2005 has “persisted for years” with the damage in the forest canopy lasting

“right up to the subsequent drought in 2010”[5].

Consequently, in the future the Amazon won’t be as efficient in storing carbon

than in the past as trees will become increasingly damaged due to the combined

effects of persistent droughts and slow recovery times.

Not only has climate variation impacted the Amazon’s ability

to act as a carbon sink. Extensive deforestation has also been a major culprit.

Indeed, if deforestation continues at this current rate most of the Amazonian

tropical forests would disappear in 50 to 100 years[6].

Currently, the Amazon deforestation is causing up to 10 percent of all

greenhouse gas emissions due to the removal of forests which would have been

able absorbed that CO2 if they were still there. Unfortunately, this

is contributing to our Earth’s rising temperatures.

In conclusion, due to human activity, the Amazon trees have

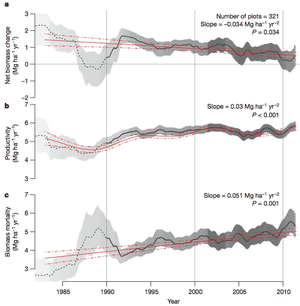

removed nearly a third less carbon in the past decade than before[7] and have suffered major changes in biomass (figure 1).

Still, the Amazon absorbs more CO2 than it releases making it a

vital carbon sink. However, if current rates of deforestation and droughts

continue at this speed, the Amazon will become permanently carbon neutral which

would disrupt our planet’s entire carbon cycle leading to catastrophic events

such as massive loss of biodiversity and even faster increases in global

temperatures.

Figure 1 the Amazon rainforest's net biomass change, productivity

and, biomass mortality over the past 25 years[8]:

Short BBC clip on the Amazon rainforest which is our planet's lungs:

Sources:

Web sources:

Research papers:

Feldpausch, T. R., et al. (2016), Amazon forest response to repeated droughts, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 30, 964–982, doi:10.1002/2015GB005133

Shukla,

J., C. Nobre, and P. Sellers. 1990. Amazon deforestation and climate change.

Science 247: 1322-25

Numerous researchers. 2015. Long-term decline of the Amazon

carbon sink. Nature 519: 344-348

[1] Feldpausch, T. R., et al. (2016), Amazon forest response to repeated droughts, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 30, 964–982, doi:10.1002/2015GB005133

[4] Feldpausch, T.

R., et al. (2016), Amazon forest response to

repeated droughts, Global Biogeochem. Cycles, 30, 964–982, doi:10.1002/2015GB005133

[6] Shukla, J., C. Nobre, and

P. Sellers. 1990. Amazon deforestation and climate change. Science 247: 1322-25

[8] Numerous researchers. 2015. Long-term

decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519: 344-348

No comments:

Post a Comment